Ethical differences between antimalarial resistance and antibacterial resistance

Researchers from the University of Oxford have written a commentary for BMJ Health arguing that that many interventions against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) treat it as an undifferentiated problem, when in fact there are morally relevant differences between microbes. They argue that ignoring these differences can cause injustice, and that interventions against antimalarial resistance, for example, should receive higher priority.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes develop the ability to survive drug treatments. A study from 2019 highlights that antibacterial resistance (ABR) caused about 1.27 million deaths and was associated with another 4.95 million deaths worldwide.

However, deaths attributable to fungal, parasitic, or viral resistance including to malaria remain unclear. In 2023, 95% of deaths related to malaria occurred in the African region, making it clear that a large proportion of population that suffers from antimalarial resistance are based in low-and-middle income countries, and are likely less privileged compared with those at risk from ABR, as ABR affects people in high income countries to a higher proportion. Researchers argue that it would be more just to give antimalarial resistance higher priority in AMR research and interventions.

Many low‑ and middle‑income countries like India, the Philippines, and Indonesia face a heavy burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR). A fair and just approach should be taken where we prioritise bacterial AMR that affects people in these countries, but we must also consider which specific microbes deserve more attention, rather than treating the problem as one big ‘battle against superbugs.

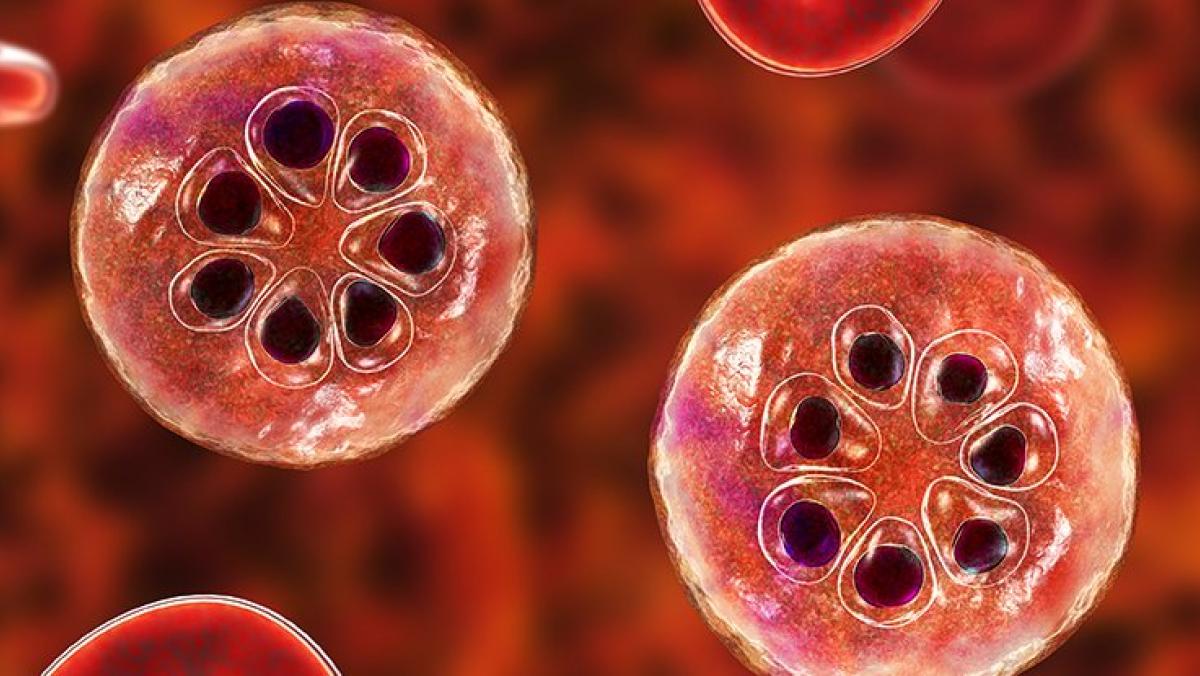

Malaria parasite - Photo credit: Dr Microbe/iStock/Getty Images

Researchers emphasised that antimalarial resistance should not be sidelined in broader AMR responses. The research calls for adjustments to resource allocation and stronger advocacy so global health interventions are fair and inclusive and do not leave communities behind.

Malaria primarily affects sub‑Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, with African children being at highest risk of mortality. This highlights the importance of giving antimalarial resistance higher priority on the research and intervention agenda. Addressing antimalarial resistance should not be sidelined in broader efforts to combat AMR.

To compare the morally relevant differences between antimalarial resistance and antibacterial resistance, the team analysed factors such as at‑risk populations, intervention goals, mortality patterns, one health issues, and treatment acceptability. Their comparative approach used examples such as chloroquine (the historical first‑line treatment for many malarias) and artemisinin resistance (parasites showing delayed clearance after treatment) to illustrate key points.

Looking forward, the team plans to continue advocating for policy changes that give antimalarial resistance appropriate attention to inform ethical resource allocation and funding decisions.